I can never leave well enough alone.

I don't usually consider this a character flaw, unless I manage to tinker something to a dead stop or make something worse than when I began messing with it. Both are rare occurrences in my experience; perhaps luck has favoured me over the years and minimized my catastrophic fuckups. At least when it comes to mechanical devices. I can't say I've been so fortunate in my social life.

In then 12 years I've owned it, I've never left my 916 alone. I wasn't about to stop messing with it now that I'd slotted in a freshly built 996 mill. In fact I considered the 996 engine the first big step towards building the machine I always wanted.

Perhaps a little background is in order to understand my compulsion.

While I'd never call the 916 unsatisfying in any configuration, it has one major flaw. Nothing wrong with the bike in particular, though as with anything else it can be improved in a lot of ways - particularly 25 years after its introduction.

No, the main flaw with the 916 is that the 916 SPS exists. You can't possibly own a standard, proletarian 916 without constantly thinking about "what it might be like if I had an SPS". It gnaws away at you over time. You hear tell of those miraculous camshafts that offer a brilliant top end rush without sacrificing midrange. You learn about the lightweight internals and hand-fitted parts contributing to a free-revving engine that is miles ahead of the standard bike. You see the dyno sheets promising 120-plus horsepower at the wheel. You learn about the near-mythic status of the SPS as a race homologation special, sold at a massive premium over the standard machine and only ever offered in North America with a waiver that forced the owner to promise never to register the bike for road use because the EPA wouldn't allow it. Europeans were luckier, able to purchase road-legal versions and the later 996S with a SPS engine.

Sure, the 996 offered that same basic engine in a more civilized package that met emissions regulations. The bottom end is similar, minus the light rods and crank and close ratio box. The SPS came with a set of 50mm exhaust headers instead of the typical 45mm items, but any back-to-back dyno tests has proven that the bigger pipes sacrifice average power below the peak for just a couple of extra ponies up top. Beyond that the pistons are the same and the heads are supposedly identical, though credible sources note that the SPS was more carefully assembled and generally flows more, while offering a hair more compression. All of that should add up to something that is close enough for most people.

I'm not most people.

After I slotted the 996 engine into my 916 and finished tuning, I had a gen-u-ine 117 hp and 70 lb/ft measured at the wheel with flawless fueling cooked up by myself on TunerPro RT after many miles of tuning and testing. A few more ponies than a standard 996 offered, easily attributed to a set of pipes, degreed cams, and the three-angle valve job performed during the rebuild. The result was a sweet running bike that retained all the character of a 916 with about 10% more of everything across the board.

That wasn't good enough. It still wasn't a SPS. That dark siren beckoned me from the abyss of the rabbit hole.

I consulted with my trusted engine builder and on-call Ducati Guru, Ken Austin. Ken was the fellow who performed the rebuild on the 996 engine after I bought it out of the trunk of a car in a gas station parking lot in Vancouver. While it turned out to be perfectly serviceable we erred on the side of caution and Ken went through the entire engine, checking every spec, blueprinting wherever feasible and setting everything to perfection.

With decades of race tuning experience and many late nights spent assembling Superbike powerplants, Ken knows how to put an engine together. He also knows how to make horsepower.

His first suggestion was a set of high-compression pistons. In Ken's experience compression is king, with virtually no downside if you know what you are doing. You get more power across the board by boosting the torque from idle to redline, without sacrificing anything like you might by chasing hot rod cams and high-rpm flow.

The stock 996 engine isn't lacking in compression as far as big V-twins go, with around 11.5:1 claimed by the factory. But more is better, and the most is best.

So after some nights spent noodling around on the internet I ended up with a set of Pistal R2000 standard-bore forged pistons on my doorstep, ordered from a supplier in Italy who still stocked them at about half the price I would have paid from a North American dealer.

At first I thought I was getting a set of 13:1 items. Which seemed unusual, because the dome was so high that the stock spark plugs wouldn't clear them. I hadn't heard about that issue from anyone who had installed the 13:1 slugs. In they went after a quick diamond hone of the bore. While I had the heads off I took them home and lapped the valves, mirror polished the combustion chambers, carved the weld beads out of the exhaust manifolds, and port-matched the inlet runners. Minor stuff but every little bit helps.

Ken finished the assembly, double checking the cam timing and valve-to-piston clearance. Everything looked good, and we maintained a relatively conservative cam timing number - advanced slightly from stock centrelines, but not so much as would provide best torque with standard compression.

Therein lies the fatal mistake most wannabe Ducati tuners make when upping compression.

On a standard engine, advancing the Strada cams 10 or more degrees on intake and exhaust provides a substantial bump in torque below the power peak without killing top end horsepower. In fact the peak power will remain virtually the same, but you can gain up to 5 hp across the curve below that (provided you adjust the fuel and ignition to suit, of course). Without getting too far into the thrilling finer technical points of cam timing, you are effectively boosting dynamic compression of the engine. Advance the cams and cranking compression increases. Retard them and the opposite happens. All without altering the static compression provided by the pistons and combustion chambers.

This is good until it isn't. It goes bad when you are running sky-high static compression ratios. Like you would with a set of Pistal pistons. Then you run into pinging, detonation, and all the nasty stuff that destroys engines in short order unless you are running 7$ a litre race fuel or detuning the ignition to the point of killing the horsepower that you were trying to gain. Neither of which I intended to do with my bike. This thing had to run happily on premium pump gas.

The solution, of course, is to not run your cams advanced into the danger zone. Follow that one critical step and you'll be golden. As I was, even after I accidentally installed Superbike race replica pistons into my Ducati.

Turns out that spark plug clearance issues aren't a problem on the 13:1 pistons. But they are on the full-fat 14:1 race pistons Pistal supplies for the 996. On those you have to run surface discharge plugs to maintain safe piston to spark plug clearance.

Oops.

Regardless of my mistake, by playing it safe with cam timing and keeping the squish set a little over 1mm I ended up with a happy engine that ran safely on 91 octane pump gas. 94 octane turned out to be unnecessary, and actually hurt power. For the record I calculated the static compression around 13.5:1 as installed, with a healthy 200 psi cranking compression on both cylinders after break-in. And zero pinging or knocking, even before I dialed in the fuel mapping.

The result was extra oomph across the range, and just enough top end to now be a bit scary to pin the throttle above 7000 rpm. I didn't dyno it after the piston install but I'd imagine it was in the low 120s and mid 70s for torque. Overall a good result with no sacrifice in driveability. Any lingering doubts about reliability were addressed by riding the piss out of the thing for 4000 miles without a hiccup, even on allegedly "premium" fuel from back country gas stations.

But... it still wasn't a SPS.

The siren kept calling.

I'd already lightened the rotating mass considerably with a 3 pound lighter flywheel we installed during the original rebuild, which would just about match the stock crank mass of a SPS. I took this a step further by installing a lightweight alloy slipper clutch and alloy clutch pack, which shaved off 3 pounds compared the all-steel setup I was running before. I didn't have a close ratio gearbox (though installing the transmission out of a 748 duplicates the ratios of the SPS should you want them) but going up 2 teeth on the back and down 1 tooth on the front made the tall gearing of the standard box livable.

The main piece of the puzzle - and the one I've desired since I bought my 916 - is a set of SPS cams. They are what gives the SPS its essential character. They are significantly higher lift (more than 1mm extra on the intake) with revised timing on the exhaust side. Duration is similar to Strada cams but overlap is altered for better high-rpm breathing. Their lobe profiles are extremely asymmetrical, obvious at a glance when comparing the opening and closing ramps. They have earned a reputation as the ultimate hot street cam for the desmoquattro, offering more power everywhere without sacrificing bottom end/midrange like the more aggressive G/A/458/Corsa-spec cams inevitably do. They are also a straight drop in for most desmoquattros, unlike the Corsa or 748R items which need extra piston clearance and different valve spacing, respectively. As a result they have been copied by most aftermarket companies, all of whom offered SPS-like cams in their catalogues at one point or another.

As you might imagine, this means that SPS cams are highly sought after and command a premium whenever they come up for sale. OEM Ducati items aren't exactly common; either they come out of a wrecked SPS or from the factory at 2500$ USD a set. About double what I paid for an entire 996 engine.

So when a set came up for sale privately for less than a grand, I snapped them up immediately. I could scarcely contain my excitement while I waited for them to arrive.

I pored over those little bumps sticks for far longer than I care to admit. I examined and re-examined their shape, the magic T1 factory codes that identify them. I lovingly chamfered the sharp edges of each lobe with a ceramic stone. They are finally mine, here, in my hands. The little pieces of unobtanium that will take my bike to the next level. Will they live up to my expectations? Will they offer everything I was promised by all those "experts" on the internet?

They aren't doing much good looking pretty on my work table. They need to be installed, pronto. I ordered up a set of adjustable alloy pulleys to dial them in properly (and shave a pound off the valvetrain mass). Then I called Ken and formulated a plan.

At this point it was late in the Fall. I wanted to get them installed before the end of the season so I could test and tune the bike and enjoy my much-hyped widgets before the snow fell.

But there was a caveat: up to this point I was running the standard 916 single injector per cylinder throttle bodies. I had come within 10% of the maximum available fuel at the torque peak after installing the high compression pistons. And that was running a 4.0 BAR fuel pressure regulator, 30% higher pressure than stock. There was no way the single injector rack would support any further modifications, not without increasing the fuel pressure to a ridiculous level.

It isn't so much that the injectors can't flow that much, it's that the time available for the fuel to get squirted in at higher RPMs is limited. Injectors are time based. Flow is constant, only the time they are opened is altered to give more or less fuel. So if you have 10 milliseconds of time available but need to squirt 13 milliseconds of fuel, you have a problem. Split that between two injectors and all is good, with each opening 6.5 ms to provide the same amount of go juice.

This is a good problem to have, because requiring more fuel means you have more torque which means you have more power. The single injector setup with stock pressure typically maxes out around 120 hp, so running out of fuel with higher fuel pressure meant I had a healthy power curve.

I scoured eBay and the forums for a while and managed to find a double-injector throttle body off a 996 with a 1.6M ECU, the only one that would be a straight swap without any major headaches. Being a dumb system where the two injectors run parallel all the time I didn't even need to modify the wiring harness, just a few keystrokes to alter the injection timing in the EPROM and away we go.

I tore the bike down and spent an evening installing the cams, pulleys and setting the valve clearances. Once those basics were done I got Ken to come over with his tools to set the cam timing, and educate me on the process. That is one thing I've never attempted myself and I was keen to learn how.

A few hours and a few beers later and we had them dialed, set to 110/110 degree centrelines based on similar setups tested by Australian Ducati tuner extraordinaire Brad Black. Incidentally I highly recommend reading each and every one of Brad's tuning reports, they are a wealth of information for anyone interested in performance tuning.

Another evening of re-assembly and twiddling to get the engine running properly with the new throttle bodies and I ride the bike out of the garage and straight onto the highway for some power pulls.

Initial impressions are muted by the lack of tuning but it's immediately apparent this thing runs hard. The intake roar, already pretty epic on a stock 916/996, takes on an even harder edged growl with the new cams. I nearly run into the back of a slow moving car when I wind it out while paying too much attention to the tachometer.

One of the greatest tools I've added to my arsenal in recent years is an Innovate MTX-L wideband AFR gauge. Compact and simple to install, I run the gauge mounted temporarily in the cockpit to monitor my air fuel ratio instantaneously on the road, rather than simply at WOT on the dyno (at 150 bucks an hour). I'd perfected the fuel map before the cam install and thought simply adding a bit extra everywhere would be sufficient to compensate.

I was wrong.

This ends up being the start of a long period of testing and tuning, with the bike being far more sensitive to rich or lean sections than before, going into a stuttering tizzy anytime the AFR dips away from ideal. I'm not sure if this is due to the cams or a peculiarity of the double injector setup, being reminded of the notorious 3500 rpm stumble present on stock 996s. I could duplicate that stumble at any point the AFR went leaner than 14:1 or richer than 12:1. It rapidly becomes clear than these cams require vastly different fueling across the board. Comparing before and after maps would suggest two totally different bikes.

It requires so much work that I end up carrying my laptop and chip burner with me on my rides, spending hours running up and down my super secret test road (conveniently located just south of one of my favourite cafes) stopping on the shoulder to make alterations and test again. One section along the route had an active construction site, and I'm sure the workers were wondering why the hell this dude on a loud red bike passed back and forth along this quiet stretch of road about three dozen times.

Wash, rinse, repeat. Perform the same process with the ignition maps, then again for the rear cylinder offset map. I end up spending quite a few days and evenings with one eye glued to my AFR gauge and a heavy laptop in my backpack, buzzing up and down the backroads around Calgary where I can run the bike wide open with minimal risk of getting caught by unsympathetic law enforcement. I'm just tuning the engine officer, need to check my AFR at full throttle...

I loved every minute of the process and the curious glances I'd elicit from passing motorists when I'd be sitting on the side of the road next to my bike with my laptop open.

But the results, oh my yes the results. Popping in these cams uncorks the full potential of this engine.

Power from 7000 rpm to redline is sparkling and strong, pulling mighty hard and picking up revs so effortlessly you'd think the stock engine had a sock shoved in the intake. Midrange between 3000 and 6000 is superb and satisfying, with a slight dip around 5500 being the only flaw in the powerband. A tiny bit of bottom end is lost below 3000, but not so much that you'll be notice unless you really look for it. The wide, linear powerband of the desmoquattro mill is retained, but overall response is harder and sharper, turning everything up to 11 and adding to the already aggressive character of the bike. You need to watch your ass because it spools up the rear tire much more readily, a fact I discovered when I exited a tight roundabout crossed-up sideways in second gear.

I've yet to get it onto the dyno since I finished my tuning, but I'd say it's easily in the 130 hp range with something around 80 lb/ft.

Good God Almighty is this thing good. It was fantastic before. Now it's spectacular.

But I still can't leave well enough alone.

With the engine and tuning right where I wanted it, what could possibly be left to mess with? In the past I'd already sorted out the suspension, the brakes, the clutch, and the miscellaneous electrical shortcomings. The only thing left to deal with is the weight.

I set about putting the bike on a diet of carbon fiber, titanium and light alloy. A Shorai battery replaced the porky stocker. I carefully calculated the most effective areas to install lighter components for maximum weight savings without wasting too much money on minuscule improvements - titanium bolts aren't exactly a cost effective way to shave weight.

Then I capped it all off with the piece-de-resistance and a modification I've coveted for a long time: a set of five-spoke BST carbon fiber wheels.

I justify splurging on these wheels by noting that I got a smoking deal on a leftover set from HPS in the UK. I paid only slightly more for BSTs than I would have paid for the cheapest set of forged aluminum OZs, about 2/3rds of what they typically retail for here in North America - including shipping and duties from overseas. I would have been stupid not to buy them. Probably.

Those wheels netted me a savings of 12 pounds, 6 per wheel. Total savings along with the other exotic bits have amounted to 30 pounds off the wet weight. Before you ask how I know that for certain, I'm obsessive enough to weigh each component I replace. The resulting spreadsheet says 29.5 pounds lost.

That's a difference you feel immediately, nevermind the massive savings in rotating mass courtesy of those beautiful wheels. The lack of inertia makes the bike feel like it has an extra 5 horsepower in the first three gears and helps counteract the typically sluggish steering inherent in the 916 chassis. Plus the huge reduction in unsprung mass helps the suspension, improving the damping control and making everything feel noticeably smoother. Win win win.

So what I have now is a 1997 Ducati 916 that is 30 pounds lighter and has 30 more horsepower. To say this thing is fun to ride is a major understatement. It is a weapon. It now has the power-to-weight ratio of a first-generation Yamaha R1, with a huge reserve of midrange below the peak. If I could travel back in time to 1997 with this thing in tow I could be king of the backroads. 130-odd horsepower at the wheel might not sound impressive in an era of ballistic 200 hp superbikes, but the quality and accessibility of the power makes this thing an absolute riot to ride in anger.

I'm goddamned thrilled with how it turned out and don't regret a single penny of the considerable sum I spent on bringing it to this level. It's not a SPS; at this point it would slay a stock SPS, and I can safely say it blows the doors off a 998 - maybe even a 999.

For now the siren has been silenced and I think I have found the bottom of this rabbit hole.

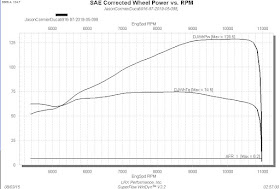

Post script: In May 2019 I finally got around to dynoing the final 996 SPS engine configuration.

The result is near-as-dammit 130 hp and 75 lb/ft. Measured on a Superflow dyno at 3500 ft elevation. I'm pretty damned pleased with the result. This is first-generation R1 horsepower out of a Desmoquattro twin running on pump gas.

Finally! Cheers Jason, well worth the wait. I'd still love to see the results of a dyno run though!

ReplyDeleteThere is little doubt you have what is, very likely, the best 916 in the world. Plus, it looks fking nuts with those wheels.

ReplyDeleteMy '97 916 motor is stock but I like reading about how far you can go with it, as I do all your other 916 posts. Would you consider publishing your worksheet of weights and/or the ranked list of effective parts to replace?

ReplyDeleteOk here we go, listing the weight saved for each item:

DeleteFlywheel 2.75 lbs saved

Quick change sprocket carrier and alloy sprocket .75 lb

Shorai battery 6.3 lb

Slip on exhausts 5.1 lb

KBike slipper clutch, Barnett basket, alloy plates 3.1 lb

BST wheels 12 lb

Carbon clutch cover .7 lb

KBike adjustable alloy cam pulleys .83 lb

Carbon v-fairing .5 lb

All the titanium and alloy bolts/nuts combined (wheel nuts, brake rotor bolts, suspension pinch bolts, a few others; probably around 50 pieces total):

a whopping .92 lb

Easy to see that ti hardware isn't very cost effective! It's also heavier than aluminum, so replacing something that is already alloy with titanium is going backwards!

I'd be happy to! I'll dig up my spreadsheet tonight and post a breakdown here in the comments.

ReplyDeleteVery good write up. I want to upgrade my 996 for race use but I'm finding sps cams impossible to find. I think with pistal pistons sps cams head work and maybe ti rods would make a stonking reliable motor

ReplyDeleteI was extremely lucky to get a set for a "reasonable" price (which I think was 1300$CAD, for comparison I paid 1500$CAD for the entire 996 engine). I can't recommend them enough if you can find them. That being said, if you are going full race you might be well served by G or R cams or something hotter like that - the SPS cams are midrange heavy and not too peaky so perfect for street but there are likely better options for race use at sustained high rpm.

Delete